Janet Mui, Head of Market Analysis, discusses new US jobs data and what this could mean for inflation, and the impact of falling oil prices.

At the end of 2023, everything rallied – and at the start of 2024, everything has sold off. This has not been an enormous shock. The fabled Santa Rally means that the S&P500 has risen in 15 out of the last 20 years. The flipside of this is that only ten of the last 20 Januarys have provided gains. When taking into account the currency exposure a UK investor suffers, this drops to eight out of the last 20 Januarys. The UK equity market is even more stark. 17 of the last 20 Decembers have seen gains, and only seven of the last 20 Januarys.

Seasonal trends do not form the bedrock of a reliable investment strategy. On average, January has been the worst month for the UK equity market but last January, stocks jumped 4.4%. As the influential investor Howard Marks remarked, “Never forget the six-foot tall man who drowned crossing the stream that was five feet deep on average.”

So, while the odds are generally slightly more favourable for December than January, this particular December saw a rally so strong and so broad that it pushed a number of stocks into overbought territory (when companies have rallied particularly sharply, they are overbought and often need to slow down or even reverse their gains).

Markets also seemed to suffer from a form of selective blindness, in which they took great cheer from the dovish central bank and were less concerned by signs of inflation persevering.

All of this meant that the early days of January were likely to see profit taking, as seems to have been the case.

Middle Eastern escalation

Another issue the markets have been comfortable overlooking is the rise of geopolitical risk. The 7 October attacks on Israel saw a sharp rise in the oil price, reflecting the risk that the attacks could begin a cycle of escalation that might eventually disrupt energy supply. In the final months of the year, though, this risk was overwhelmed by the greater risk that the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) might be oversupplying energy to the global economy, and that it might struggle to restrict supply in the face of price falls. During 2023, Saudi Arabia restricted its own supply to support prices for OPEC as a whole, but continuing to do so indefinitely would undermine the point of the OPEC operating as a cartel.

So, oil was weak at the end of last year, contributing to the increasing hopes of a soft landing for the global economy. But it picked up over the last week as the threat of escalation in the Middle East has returned. Prior to last week, we already understood that Houthi rebels, who have been fighting a civil war in Yemen for the last decade, had begun harassing shipping navigating the Red Sea through missile and drone attacks and attempted boardings. Over the New Year’s weekend, the US Navy intervened to defend shipping, was fired upon, and ended up sinking Houthi vessels. However, this action has not deterred Houthi attacks.

As discussed, the risk to oil is that a broader Middle Eastern conflict emerges from the current proxy wars involving Iranian-backed groups operating throughout the region. Over the course of last week, aside from activity in Yemen, the US struck Iran-backed militia in Baghdad with a drone strike and two bombs were detonated in Iran.

Fretting over freight rates

There are, however, more direct consequences of the Houthi harassment of shipping. The Red Sea is the gateway to the Suez Canal, which forms a well-travelled shipping artery between Asia and Europe. 12% of global trade travels this route each year and disruptions (as occurred when the vessel Ever Given blocked the canal in 2021) have serious repercussions for supply chains. It can mean that shipping either has to travel a further ten days around the southern cape of Africa, or for urgent transit, shippers will redemand higher transit fees to compensate them for the heightened risk of navigating the Red Sea.

Freight rates have risen sharply, despite the good fortune that these attacks began as the peak season was drawing to a close. Demand will, however, pick up, particularly ahead of Chinese New Year in mid-February. Unfortunately, they also come at a time when the water level in the Panama Canal is unusually low, restricting its use for pan-American transit. Anecdotal reports have suggested that freight rates have risen to multiples of the rates being charged a few weeks ago.

Should this trend continue, those costs will be reflected in consumer goods prices. Consumer goods have been an important source of disinflation over the last few months despite services costs seeming to remain persistently high. As a rule, goods prices in developed economies will likely reflect some combination raw material, transport and currency costs (recent weakness of the dollar will push up imported goods costs). Beyond this, goods may be over or under supplied, and after the surge of pandemic demand, consumer goods production outstripped demand, leading to a need for destocking, a process which seems to be coming to an end.

By contrast, a lot of services prices reflect wages. These have moderated in some regions (the US) more than others (the UK and Europe). But services prices have been slower to decline.

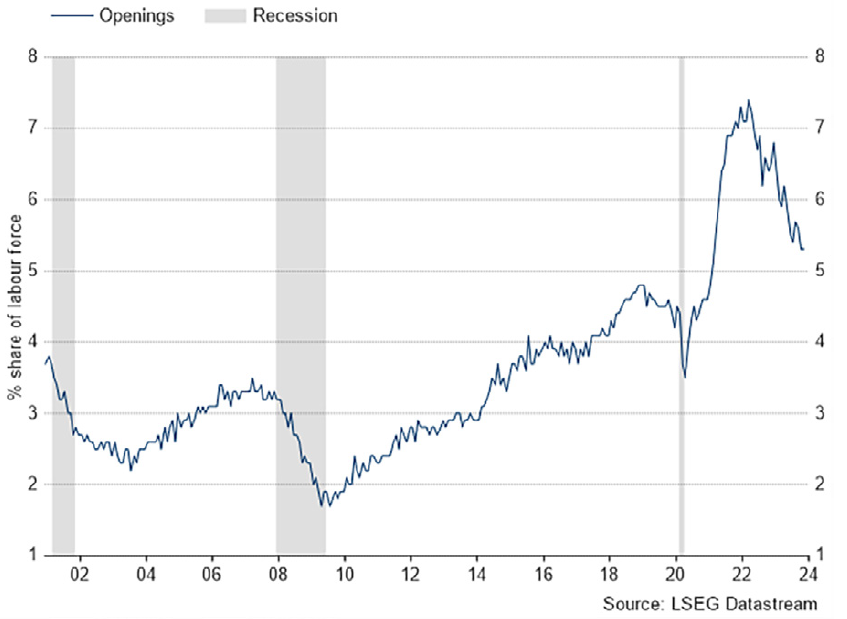

January’s jobs report

The US labour market was the main source of economic news last week. An ideal scenario would be one in which the inflationary pressures (slowing wage inflation) ease whilst employment levels remain high enough to keep the economy going. Early last week, we learnt that the number of job openings continued to decrease (albeit marginally), consistent with the idea of a loosening jobs market and a gradual decline in wage pressures. Last Thursday’s jobless claims data suggested that very few people were losing their jobs. This was all in keeping with the case for soft economic landing.

Friday saw more employment data which muddied the waters a little. Jobs growth was strong and should be good for growth, as long as it isn’t inflationary. But in December, wages did rise faster than expected and the unemployment rate stayed low at 3.7%. The labour force participation rate fell to its lowest in almost a year. These data will give the Federal Reserve some reason to fret over how fast inflation will decline in the future.

So, it has been a rough start to the New Year, but that would be expected given the strong finish to last year. Looking ahead, investors will be looking for evidence that tensions de-escalate in the Middle East. At home, they will want reassurance that the US labour market is not too hot to drive to prompt inflation, whilst also not being too cold so it provokes a recession.